a model for his PBS documentary. We were so inspired by the story behind the

this bridge we agreed right away to do it!

This is an amazing project.

We are scheduled to start building The Ashtabula bridge in September.

We want to let everyone know that they can be a part of history!

This is a non-profit organization that will be producing the documentary. Any donations will be greatly appreciated!

For for information on this project please click on the link below.

http://www.indiegogo.com/engineering-tragedy?contribution_success=true&a=889180

The Story

Engineering Tragedy is the story about the worst railroad bridge and train

disaster in United States history. It happened in Ashtabula, Ohio on December

29, 1876 during a raging blizzard. In this town off the shores of Lake Erie, an

all-iron railroad bridge collapsed sending a luxury train, The Pacific Express

No. 5, plummeting 70ft into a frozen river. Of the172 souls that were on board,

only 75 survived, most with serious injuries. Of the 97 who perished, 47 were

identified, 50 were unidentifiable. This story has been lost in the pages of

history and our team wants to bring it back to life.

Charles Collins – Railroad Chief Engineer

Charles Collins, the Engineer in Charge, was the man responsible for

overseeing bridge inspections for the entire line. Unbelievably, Stone did not

include Collins in any aspect of the bridge’s design, construction, or erection.

Perhaps that’s the reason Collins took such little interest in the bridge.

Placed in a difficult situation, Collins was charged with the maintenance and

care of a long, all iron bridge when he knew little about its unique technical

requirements. A conscientious and sensitive man, the grief over this tragedy

almost overwhelmed him. There were reports he wept bitterly when he saw the

aftermath of the crash

The Storm and the Train

The Pacific Express No. 5’s journey began in Buffalo, NY. She followed the

Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway line southwest toward Ashtabula.

Although trains were rolling as usual, the weather certainly hampered travel and

delayed many routes. Winters off the shores of Lake Erie where Ashtabula, Ohio

is located are brutal. The night the accident occurred, the entire railroad line

was being pummeled with blizzard strength wind and heavy, blinding snow.

The train traveling the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern railway that day was

a luxury one consisting of two engines, the Socrates and the Columbia - the

second engine was added in Erie, Pa. She had two express cars, two baggage cars,

two day passenger coaches, a smoking car, a drawing-room car called "Yokahama;"

the New York sleeper named "Palatine;" the Boston sleeper named "City of

Buffalo;" the Louisville sleeper called “Osceo.” The Lake Shore and Michigan

Southern railroad company spared no expense on this train. All who rode her did

so in unprecedented comfort.

The Passengers

The unsuspecting passengers that rode on the No. 5 during the holiday season

came from all walks of life and from all over the country. By all reports, the

train had a festive atmosphere in spite of the horrible weather conditions.

Several passengers were notable for either who they were prior to the accident

or for what they did after the accident. One such passenger was Phillip Bliss.

The beloved hymn writer and singer was well-known at the time for writing well

over 300 songs. He was on his way to Chicago to meet the famous evangelist,

Dwight L. Moody. Although Bliss’s voice and creative mind were silenced that

night, his songs are forever sung, even to this day, in churches throughout the

world.

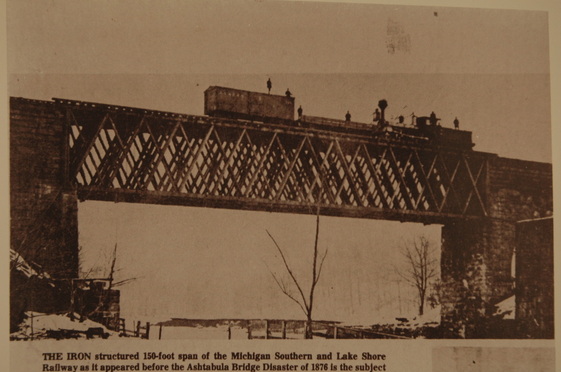

Amasa Stone – Railroad President and Bridge Designer

The Ashtabula bridge designer, Amasa Stone, was the President of the Lake

Shore Michigan Southern Railroad – Cleveland and Erie Division from 1856 to

1867. During his Presidency, he decided to take a well-established wooden

bridge pattern (the Howe Truss) and use it as the pattern for an all iron

bridge. He designed this bridge without the approval of any competent engineers

with iron bridge experience and against the protest of the engineer who was

hired to draft the drawings. Pushing the limits of design standards of the day,

this all-iron bridge was the longest ever built in America at the time. It was

154ft long from abutment to abutment, making it an even riskier endeavor since

the iron braces were so heavy.

Bridge Construction and Erection

Construction and erection of the lengthy, all-iron bridge took a year. It was

taken down and reassembled several times before it was finally completed in

1865. During the erection of the bridge, it failed twice to bear its own

weight. Because of these failures, modifications had to be made. However, these

modifications would, in fact, make the bridge perilously unstable over time.

The Collapse and Crash

At 7:27 p.m. the No. 5 rounded the final bend. Running between 10 to 15 miles

per hour, she began her slow crawl across the bridge. At first the crossing

proceeded normally. The bridge creaked as always, but held as the Socrates, the

Columbia, and then the first few cars pushed forward onto the north side of the

bridge. At 7:28 p.m. the engineer of the Socrates, Dan McGuire, heard the

distinct sound of a loud crack. He knew immediately something was wrong,

terribly wrong.

The bridge was breaking apart. The engineer of the Socrates pulled the

throttle and ran his engine the remaining few feet to the abutment and to

safety. The other cars were dragged forward when the second engine, The

Columbia, broke from the Socrates, crashed into the abutment, and fell in the

gorge. Passengers were jostled and thrown about by a violent series of bumps

when the cars derailed and the track disintegrated underneath them. Then there

was darkness…silence…falling. Cars began to crash one by one into the frozen

creek. It was a sickening and horrifying sound as the first cars slammed into

the gorge, then the rest, falling or being launched off the edge, struck the car

in front of it.

The Fire

Many who escaped the wreck did so in the first few precious minutes before

any rescuers arrived. Although a few rescuers got to the scene quickly, it would

take between 30 minutes to one hour after the fire bell rang for citizens to get

to the accident site. While straining against the blizzard strength winds and

trudging through high drifts, sadly, some became so fatigued they simply

couldn't continue.

What made the crash even more tragic was the fire that started on the east

side of the bridge within minutes of the crash from the overturned stoves used

to heat the passenger cars: Stoves, incidentally, that didn’t meet the safety

standards of the day. In addition, during the rescue the Fire Chief, G.A. Knapp,

was so inept that he failed to take command of the scene. As a result, two fire

engines sat idly by while the wreck burned from one end to the other, consuming

everything in its path.

Heroes and Villains

As in all disasters, heroes always emerge and this one was no different.

Citizens formed a bucket brigade in a vain attempt to control the fire. Others

valiantly braved the fire and ice to help victims to safety. Citizens even

opened their homes to be used as make shift emergency rooms. One heroine was a

passenger. Miss Marion Shepard, of Ripon, Wisconsin, a young woman traveling

alone on this frightful night, was hailed by a fellow passenger as one of the

bravest women he ever met. Credited with unusual bravery in the face of danger,

she was one of many who risked her life to help others.

Thieves also emerged out of the crowd. By far one of the most troubling

aspects of this tragedy, was that some men whose hearts were dark came crawling

out of the woods and stole from the innocent and hurting survivors. They

actually robbed victims while pretending to help. There were many, many heroes

on that dreadful night, but the amount of thievery done would cast a long, dark

shadow over Ashtabula for years to come.

Investigations

Similar to the Titanic's sinking, the crash of this luxury train would prove

to be more than just a tragic accident. Three separate investigations were

conducted. One by a Coroner’s Jury formed with citizens of Ashtabula under the

direction of the acting coroner, Edward W. Richards. The other was a joint

investigation by a special committee of the Ohio Legislature and the American

Society of Engineers. All three found serious problems in the design,

construction, and erection of the bridge. The Coroner’s Jury would also conclude

that the fire was ultimately the fault of the railroad company, and that the

Fire Chief and first responders should also hold some blame.

Murder and Suicide

This disaster would claim two more victims in the days and years to come.

Sadly, hours after testifying before a special committee of the Ohio Legislature

about his role in the bridge collapse, Charles Collins was murdered. Still

shrouded in mystery, his murder remains unsolved. However, after our

investigation, motives have surfaced that may help solve this 135 year old

crime.

Blame and scorn for this disaster would forever stain Amasa Stone’s

professional reputation and haunt him for the rest of his days. Many believe it

was one of the reasons he would commit suicide seven years after this horrifying

crash.

The Aftermath

After the Ashtabula tragedy, no bridges of steel or iron were ever built

using the design that Stone created in which individual components acted

independently to maintain structural integrity. In addition, the federal

government created the Interstate Commerce Commission whose original purpose was

to regulate safety and investigate accidents of the American railroad

companies.

While cities of similar size like Lorain and Cleveland continued to grow,

Ashtabula’s growth was almost completely halted as a direct result of this

disaster. She saw no significant growth until the early 20th century. Yet, the

citizens of Ashtabula would rally in spite of their grief and build the

Ashtabula General Hospital a quarter of a mile north of the bridge disaster

site. This was a positive response to the lack of medical facilities available

to care for the wounded passengers.

Approximately 10 years after the disaster, the Lake Shore & Michigan

Southern finally adopted the use of steam heat in all passenger cars to replace

the dangerous wood/coal fueled stoves, which overturned and started the inferno

that claimed so many victims in this tragedy.

This documentary, Engineering Tragedy: The Ashtabula Train Disaster, brings

to life a story that once captivated the nation and changed a town forever.

For more information about this story, to meet our team and follow the

production go to http://www.engineeringtragedy.com

Website to Promo:

http://www.indiegogo.com/engineering-tragedy?contribution_success=true&a=889180

RSS Feed

RSS Feed